The 1918 “Spanish flu” and my grandparents: Lessons from a pandemic

I am probably one of the  very few nowadays to have a “direct connection” with the 1918 “Spanish flu” pandemic, in that I had quite long conversations about it with my grandmother. Her husband, Ernest Belton, died of the disease in November, 1918. She was then seven months pregnant with Rose, my aunt. This picture shows my grandparents, with Nen their eldest daughter, in 1911 or 1912.

very few nowadays to have a “direct connection” with the 1918 “Spanish flu” pandemic, in that I had quite long conversations about it with my grandmother. Her husband, Ernest Belton, died of the disease in November, 1918. She was then seven months pregnant with Rose, my aunt. This picture shows my grandparents, with Nen their eldest daughter, in 1911 or 1912.

Gran told me that her husband had woken up one day feeling a bit worse for wear and died in her lap the very same evening – that was how virulent the 1918 pandemic was. At the time of his death, Nen was 7 years old, Ernest 6, and my father Stanley just 4. Rose was born two months later in January, 1919.

The Beltons were a working-class family with no private resources and no Welfare State to support them. My grandfather was a tram driver. They lived in tenement blocks in, variously, the East End and Islington. I don’t recall whether my grandmother had needed to work before Ernest’s death (our chats were in the late 1940s and 1950s), but, after his death, she certainly had to work daytimes as a seamstress in the big Regent Street store Dickins & Jones and in her spare time (with 4 children, aged 0-7!) as a domestic cleaner.

There was no widow’s allowance, indeed the Widows’, Orphans’ and Old Age Contributory Benefits Act did not come into force until 1925, but even then widows had to be over 45 to qualify for ten shillings (50P) per week. But gran was in her late twenties. She used to tell me that she regularly had to pawn her wedding ring for a shilling (literal but meaningless modern comparison is 5P), and, as I recall, redeemed it for a shilling and one farthing (quarter of an old penny, which in modern terms would be an interest rate of just less than 2% per week or 100% p.a.). As a sparky 10 year-old, I recall arguing with her that if only she scrimped and scraped for a week she would save farthing after farthing, but she told me that things didn’t work out like that – I never quite understood that argument then but perhaps I am getting old enough to work it out now!

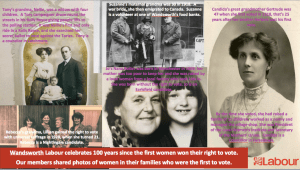

Clearly, this kind of life was impossible without very strong, informal, community bonds. Women in particular must have shared endless family tasks and, most particularly, childcare duties. The early scenes of working-class life in the East End in Sarah Gavron’s film Suffragette (2015) struck me as having very much the same flavour as my grandmother’s stories. If you’ve not seen the film, I highly recommend it. The leaflet pictured below was produced by Wandsworth Labour Parties, two years ago, to commemorate the first centenary of the women’s suffrage. You can see it includes the picture of my grandparents.

Gran couldn’t afford the farthing bus fare from Islington to Oxford Circus and so walked every day, come rain come shine. The 20s might have been the “Roaring Twenties” for some but not for the British working class. In 1926 came the General Strike and three years later, in 1929, the Wall Street Crash. Just when my grandmother might have expected my aunts and uncles to contribute to the family income, they were finding it difficult to get any job at all.

My father turned out to be a bright lad and in 1929 won a scholarship to Christ’s Hospital, which according to Wikipedia was, and is, unique amongst British “public schools” in that “School fees are paid on a means-tested basis, with substantial subsidies paid by the school or their benefactors, so that pupils from all walks of life are able to have private education that would otherwise be beyond the means of their parents”. But, even with the subsidies, the fees were too much for Nan and so, Stan, aged 14, got a job as a post office messenger boy.

It is no wonder that, for the working-classes, solidarity was, and still is, such an article of faith; it is also no wonder that trade union solidarity, perhaps most explicitly the closed shop, was so important to the labour movement. (The “closed shop” was the name used to describe the practice of enforcing trade union membership on to a workforce; it was “organised labour’s” chief weapon against “the bosses”. The effective abolition of the closed shop was one of the main Thatcher “reforms”, and look, how weak organised labour has been since then!)

My father did quite well for himself and so, thirty plus years later, he could afford to contribute his element of the major county award, which I got when going to Oxford University from a state school. Just enough of Home Counties patina and Oxford rubbed off on me, for me at times to be accused by Tory councillors, of being a class ‘traitor’. They thought me to be sufficient of a toff to have “let the side down” by supporting the Labour Party. How wrong they were and are; and how much I loathe what the Tories collectively have done to working-class life in this country.

To a considerable extent led by Wandsworth Council’s 1978 and 1982 intake of Tories, the Tories, nationally, have systematically coarsened and debased the working classes. Council house sales and the “right to buy” were part of the relentless Tory attacks on subsidised, community-owned housing – attacks which undermined the security and stability of many working-class communities. They followed that up with a policy of compulsory competitive tendering for manual labour; a policy, which cruelly and viciously squeezed the dignity out of so many jobs and coarsened our culture with crude ‘value for money’ measures, usually resulting in worsening pay and conditions, and eventually leading to the gig economy.

What very few people understood, however, was that the systemic changes introduced by the Tories could not be neatly controlled so as to affect only working-class communities and values. The digital revolution has helped to undermine very much more than simply manual jobs; the “loads-of-money” crudities of city slickers began to undermine all kinds of societal and communal values.

At the height of Wandsworth’s service privatisation, I quoted the great seventeenth century Norfolk protest song to Wandsworth’s Chief Executive, Albert Newman,

“The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

But leaves the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from off the goose.”

He only half-jokingly responded that Wandsworth Council needed to become more like the man who stole the common. What Albert Newman was doing, however half-heartedly, was recognising the Council’s part in undermining the social and communal solidarity of our society.

If nothing else, this ghastly pandemic could restore our faith in well-funded, community focused services; undermine the status, privilege and arrogance of the super-rich; restore belief in a redistributive tax and social system; re-invigorate community; and provide a springboard for voluntary action.

In the twenty years after the 1918 “flu epidemic”, Europe’s real political battle became one between social democracy and the two very different forms of totalitarianism, Stalinism and Nazism. Today, a hundred years later, we must fight for the victory of a diverse and democratic polity exercised in most of Europe (and elsewhere) against the nationalistic autocracies we see in Moscow, Beijing, much of the Middle East and, frighteningly, maybe, until recently, even Washington. But equally we need to fight to ensure that we win a social democratic democracy, not the aggressive individualistic dog-eat-dog version resulting from neo-liberalism.

Tony Belton, 17th November, 2020

Are you the Tony Belton I knew when we lived at Ashcombe Road, Wimbledon? I later caught up with him as he had a second-hand book and magazine shop in Abbey Parade, Merton. We played tennis but he usually beat me!

Not me, Ken, but pleased that you have seen my newsletter.